He opened his Emille Museum (named after the legendary Shilla-dynasty bronze bell, a

masterwork of Korean artisanship), in Seoul in 1968, but was oppressed by successive

military regimes. A breakthrough came in the late 1970's when he was allowed to hold a

major exhibition of folk-tiger paintings which then toured the USA and Europe. By then he

owned the world's largest collection of traditional Korean folk paintings [minhwa], created

by anonymous artists within the last three centuries. They included wonderfully imaginative

depictions of mythical animals such as dragons, Mountain-spirits and other Shamanic deities.

Closest to Horae's heart were the surrealistic folk-paintings of tigers, such a quintessentially

Korean art-form, both by themselves and playing staring roles in San-shin paintings and

statues. Crazy-but-friendly-looking tigers from his collection became the inspiration for the

"Hodori", the 1988 Seoul Olympics' mascot (designed by Kim Hyun, a close friend of his); Zo

Zayong's personal obsession ended up as the ubiquitous symbol of Korea's finest hour.

masterwork of Korean artisanship), in Seoul in 1968, but was oppressed by successive

military regimes. A breakthrough came in the late 1970's when he was allowed to hold a

major exhibition of folk-tiger paintings which then toured the USA and Europe. By then he

owned the world's largest collection of traditional Korean folk paintings [minhwa], created

by anonymous artists within the last three centuries. They included wonderfully imaginative

depictions of mythical animals such as dragons, Mountain-spirits and other Shamanic deities.

Closest to Horae's heart were the surrealistic folk-paintings of tigers, such a quintessentially

Korean art-form, both by themselves and playing staring roles in San-shin paintings and

statues. Crazy-but-friendly-looking tigers from his collection became the inspiration for the

"Hodori", the 1988 Seoul Olympics' mascot (designed by Kim Hyun, a close friend of his); Zo

Zayong's personal obsession ended up as the ubiquitous symbol of Korea's finest hour.

The Korea Times reported him saying in 1998: "Like the

dokkaebi, tigers were supposed to expel evil spirits. But look

at them! They're so retarded! They aren't scary at all. They

are more funny-looking, and you want to laugh at them.

That is the unique thing about Korean folk paintings and the

tigers in them. Though they are supposed to be about a

serious subject like the mountain god, the paintings are

lovable and you can laugh and feel affection towards them."

In 1983 Zo moved with his wife to the southern slope of high

craggy mountains in the center of South Korea -- partly to

escape official harassment and partly to live in harmony with

nature, closer to the villages. He became known as the

Tiger of the 'Remote-From-the-Mundane-World Mountains'

[Sogni-san, a National Park in North Chungcheong Province].

He claimed to have moved there because he "found the

Sam-shin living up on the Cheon-hwang-bong".

Using his studies of ancient times and architectural skills, he

built a proper Emille Museum building and a compound of

shrines, firepits and thatched huts that modeled those lived

in by Korean ancestors more two thousand years ago. He

held educational festivals in this compound, teaching bus-

loads of children, farmers and international groups about

the practices and spirit of Korean folk-traditions.

The events often climaxed with masked dancing around

a bonfire to samul-nori drumming, in the style of ancient

exorcisms of harmful spirits.

dokkaebi, tigers were supposed to expel evil spirits. But look

at them! They're so retarded! They aren't scary at all. They

are more funny-looking, and you want to laugh at them.

That is the unique thing about Korean folk paintings and the

tigers in them. Though they are supposed to be about a

serious subject like the mountain god, the paintings are

lovable and you can laugh and feel affection towards them."

In 1983 Zo moved with his wife to the southern slope of high

craggy mountains in the center of South Korea -- partly to

escape official harassment and partly to live in harmony with

nature, closer to the villages. He became known as the

Tiger of the 'Remote-From-the-Mundane-World Mountains'

[Sogni-san, a National Park in North Chungcheong Province].

He claimed to have moved there because he "found the

Sam-shin living up on the Cheon-hwang-bong".

Using his studies of ancient times and architectural skills, he

built a proper Emille Museum building and a compound of

shrines, firepits and thatched huts that modeled those lived

in by Korean ancestors more two thousand years ago. He

held educational festivals in this compound, teaching bus-

loads of children, farmers and international groups about

the practices and spirit of Korean folk-traditions.

The events often climaxed with masked dancing around

a bonfire to samul-nori drumming, in the style of ancient

exorcisms of harmful spirits.

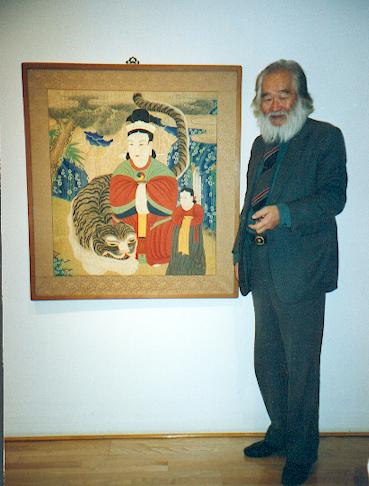

Dr. Zo at his Insa-dong exhibition in January 1998.

He is standing with one of his "new" San-shin

paintings, showing a female San-shin (a

mountain-goddess), which is a very rare motif.

He is standing with one of his "new" San-shin

paintings, showing a female San-shin (a

mountain-goddess), which is a very rare motif.

By 1990, following the Olympics, official attitudes had changed and his collection

became regarded as a national treasure, exemplifying a truly unique Korean spirit.

Horae started up what he called the "Old Village Movement", traveling the countryside

seeking surviving tutelary shrines, trying to inspire the remaining residents to maintain

them and revive old ritual-festivals at them. He tried to educate young Koreans about

their ancient traditions and inspire them to respect them. Sometimes after years of

gentle prodding and providing support he was successful; sometimes he wasn't and

that deeply disappointed him.

In about 1987 Horae founded the "Sam-shin Association", dedicated to furthering his

projects, with a hundred members (mostly younger Koreans). After decades of primary

devotion to tigers and the Mountain-spirit [San-shin], he turned his studies towards the

old Shamanic deity the Triple-spirits [Sam-shin]. In these triplet-gods-of-conception he

found a trinity-symbol that he could associate with other religious trinities across Korean

culture, from the Christian Father-Son-Spirit and the Buddhist Buddha-Dharma-Sangha

to the Neo-Confucian Heaven-Earth-Humanity [Cheon-Ji-In]. In their grandmother-

goddess-of-lifespan [Samshin-halmoni] he found a unifying principle that could be used

to represent the spirit of the entire Korean nation from King Dan-gun onwards.

became regarded as a national treasure, exemplifying a truly unique Korean spirit.

Horae started up what he called the "Old Village Movement", traveling the countryside

seeking surviving tutelary shrines, trying to inspire the remaining residents to maintain

them and revive old ritual-festivals at them. He tried to educate young Koreans about

their ancient traditions and inspire them to respect them. Sometimes after years of

gentle prodding and providing support he was successful; sometimes he wasn't and

that deeply disappointed him.

In about 1987 Horae founded the "Sam-shin Association", dedicated to furthering his

projects, with a hundred members (mostly younger Koreans). After decades of primary

devotion to tigers and the Mountain-spirit [San-shin], he turned his studies towards the

old Shamanic deity the Triple-spirits [Sam-shin]. In these triplet-gods-of-conception he

found a trinity-symbol that he could associate with other religious trinities across Korean

culture, from the Christian Father-Son-Spirit and the Buddhist Buddha-Dharma-Sangha

to the Neo-Confucian Heaven-Earth-Humanity [Cheon-Ji-In]. In their grandmother-

goddess-of-lifespan [Samshin-halmoni] he found a unifying principle that could be used

to represent the spirit of the entire Korean nation from King Dan-gun onwards.

Towards the end of his life, his religious thought reached its full maturity; he carved,

painted and enshrined Korea's three main folk deities together as an expanded

Sam-shin. He placed the San-shin [Mountain-spirit] and the Chil-seong [Seven stars

of the Big Dipper / Ursa Major] flanking the central Sam-shin-halmoni as a grand

icon of the "Earth-Humanity-Heaven" trinity.

painted and enshrined Korea's three main folk deities together as an expanded

Sam-shin. He placed the San-shin [Mountain-spirit] and the Chil-seong [Seven stars

of the Big Dipper / Ursa Major] flanking the central Sam-shin-halmoni as a grand

icon of the "Earth-Humanity-Heaven" trinity.

Zo returned to a focus on the Mountain-spirit

theme with a successful exhibition in Insa-dong of

a half-dozen of his own new San-shin's (copying

from the old ones in his collection). It was held in

January of 1998, just after Korea entered the

"IMF-crisis-era" economic troubles and just two

years before his untimely death.

theme with a successful exhibition in Insa-dong of

a half-dozen of his own new San-shin's (copying

from the old ones in his collection). It was held in

January of 1998, just after Korea entered the

"IMF-crisis-era" economic troubles and just two

years before his untimely death.

He was quoted: "One day, I had a dream and a

voice told me, 'Why use the strength of others? Try

to paint by yourself.' So I did the three paintings on

that wall the next day... They are our rendition of

the Mountain Spirit and Korean Tiger for the 21st

century. The mountain spirit isn't a dead belief

and these folk paintings aren't a dead tradition,

they are still the heart-beat of our culture."

voice told me, 'Why use the strength of others? Try

to paint by yourself.' So I did the three paintings on

that wall the next day... They are our rendition of

the Mountain Spirit and Korean Tiger for the 21st

century. The mountain spirit isn't a dead belief

and these folk paintings aren't a dead tradition,

they are still the heart-beat of our culture."

RIGHT: the Chil-seong - Sam-shin-

halmoni (on a turtle) - San-shin trinity,

designed by Zo, now in front of his

tomb in that valley.

BELOW: the San-shin from the first

trinity Zo painted himself and set up

behind his house below the Tiger-

head bawi.

halmoni (on a turtle) - San-shin trinity,

designed by Zo, now in front of his

tomb in that valley.

BELOW: the San-shin from the first

trinity Zo painted himself and set up

behind his house below the Tiger-

head bawi.